freshly squeezed #1

juicy takes on diginobs and why we should forgive Kirstie Allsopp

Hey there,

It’s been a while hasn’t it. I kind of disappeared midway through last year.

I’ve been busy. I changed jobs, I moved house and best of all, I had a bit more fun after the bumpy ride that was the last couple of years. If you are curious, I wrote about my 2021 here.

Anyway, I’m back with Season 2 of my newsletter.

With freshly squeezed, I’m going to be sharing juicy observations on life, culture and society, every fortnight.

What can you expect? Short takes for the most part and occasionally, a slightly longer piece of writing. In terms of a theme, one may emerge retrospectively. But for now, the canvas is intentionally broad to begin with.

I’m unashamedly writing for fun and for myself. But in doing so, I hope that you find something delightful in what I share.

This may not be what you signed up for. The work of Between Black and White is unfinished. But I’ve found myself wanting to write about so much more than politics.

I hope you’ll continue along with me on this journey. But I appreciate your eyeballs are a precious, time poor and over-targeted resource, so please do feel free to unsubscribe.

For the rest of you juice drinkers, read on.

Sunil

quick & juicy takes

i. the rise of the diginobs & the new left-behind

I’m officially what my co-founder calls a “diginob.” Her derogatory term for a digital nomad.

I’ve recently joined a remote-first startup. I live in London. But now my office can be pretty much anywhere I want it to be.

It’s part of a wider trend that many are experiencing: our physical and digital worlds are increasingly separate. And it’s been accelerated by the pandemic. Ben Thompson, author of Stratechery, labelled it the “The Great Bifurcation.”

He writes:

… to use myself as an example, my physical reality is defined by my life in Taiwan with my family; the majority of my time and energy, though, is online, defined by interactions with friends, co-workers, and customers scattered all over the world.

For a long time I felt somewhat unique in this regard, but COVID has made my longstanding reality the norm for many more people. Their physical world is defined by their family and hometown, which no longer needs to be near their work, which is entirely online; everything from friends to entertainment has followed the same path.

Part of me feels liberated by these changes.

I can see my family more. I can stay with friends who live abroad and work remotely in a way that felt impossible only a mere twenty-four months ago.

And I’ve found belonging in online communities like Foster in a way that I haven’t elsewhere.

But despite new possibilities being opened up by the shift to remote work, many digital nomads still yearn for IRL (in real life) community.

That’s why organisations like Creator Cabins, a decentralised city for online creators, have sprung up. Another is Launch House, which offers residency programmes targeting entrepreneurs. Upon acceptance, applicants live in swanky digs.

Both of these organisations are targeting people who previously may have headed to Silicon Valley. One of the co-founders of Launch House said,

All that kind of 'that’s what silicon valley is' has basically died after COVID. We think the new Silicon Valley is distributed.

And there is no doubt a change is taking place. Just look at these pictures of San Francisco in peak rush hour:

I hear you. That’s San Francisco. They’re a bunch of weirdos. Does this actually mean anything for me where I am?

San Francisco and America may be home to the most extreme manifestations of these trends.

But we’ve been down this road before. American startups upending how we live.

We’re all familiar with the likes of Airbnb, Amazon and Uber.

Let’s do a quiz:

How many times have you purchased something from one of these companies because it’s easier than the alternatives?

Have you actually come to know someone properly who works for one of these companies while paying for their services?

Our collective answer to question one lies in the tens, if not hundreds, of thousands. And I’m confident the answer to question two is a big fat zero (or at the very most, a single digit).

I interviewed my grandma last year to record our family’s oral history. I was struck by how she knew the names of people who provided many of the services that we now purchase online by default. And they popped up in stories over several years.

Today, the kind of continuity my grandma experienced has given way to transience. In automating the friction out of our lives, these types of services have made it easier for us to disconnect from our local communities.

The shift to remote work has followed, enabled by digital technology and accelerated by the pandemic. This has again allowed those who are able to rethink how they live, to go as far as to reconsider where they live.

I remember coming to London in my mid-twenties. It was the done thing. I unconsciously assimilated the belief that London was where I needed to be to build my career. But armed with a laptop and a good internet connection, that no longer necessarily holds true.

And digital nomads are increasingly trying out different places for remote work. It’s marketed as a win-win. The nomads work in beautiful places, which get an economic boost from their presence.

But there are familiar echoes of disconnection between digital nomads and the places they visit that puncture these rosy narratives.

A recent Sifted article, for example, gently lifted the lid on the presence of digital nomads in the Canary Islands and Madeira, both popular choices for remote work in Europe.

One nomad admitted, “I don’t think nomads know how to give back by default.”

It’s a theme that I’ve seen pop off on my Twitter feed more than once.

It’s entirely possible to be in a place for a long time, but still not truly live there.

So what might be next?

Well, remember Creator Cabins and Launch House?

People who share similar interests, jobs and values living together.

It’s a subtle shift from just remote working in a nice place. These kinds of startups are building infrastructure to serve the new nomadic elites.

But this trend won’t be limited to purpose-built fancy buildings.

Balaji Srinivasan, an influential entrepreneur and investor, has predicted the rise of the “network state.”

With capitalism, we vote with our wallets. With democracy, we vote with our ballots. With migration, we vote with our feet.

Most of us are familiar with the first two, but many of us are less experienced when it comes to migration. No longer.

Balaji foresees a future where city states and institutions will be built with all three in mind. Designed to attract nomadic elites with capital, ideas and talent.

If this sounds fanciful, an early draft of this story is currently being written in Miami, which the Financial Times recently described as “the most important city in America.”

But it’s not difficult to see how this might go wrong.

The community “with a greater degree of alignment” that Balaji speaks of may be one that is agreeable to live within. But if societies are fragmented and separated in such a way, the phrase “left-behind” will take on a whole new meaning.

If this seems far-fetched, recall how the pandemic exposed the brutal reality of our ability to lead very different lives from our fellow citizens. Not for nothing did I write in late 2020 that:

Our socially distanced today may foreshadow a structurally distanced tomorrow, with networks becoming increasingly segregated on the basis of economics, politics or even their social outlook.

You also may think, so what? Some people move in search of a better life. That’s always happened.

Yes, that’s true, but remember those pictures of empty San Francisco? What happens to the tax base and infrastructure when some of the highest-earning workers depart? The former shrinks and the latter gradually erodes in quality.

So if such a future came to be at scale, it’d affect us all in some way.

While it’s still early in terms of how this all plays out, the rise of the diginobs may actually be a precursor to a new fault-line, one that will shape the rest of the twenty-first century to come.

If you like science fiction movies and want to see a really extreme (and silly) version of what such a world might look like, check out Elysium.👇🏾

What do you think? Agree? Disagree? Hit reply with your thoughts. I’ll share the most interesting ones in the next edition of freshly squeezed.

ii. why we will all become Kirstie Allsopp

Only 28% of young people aged 25-34 own a home. In 1989, that figure was 51%.

But young people can afford a home. That’s according to Kirstie Allsopp, the co-presenter of Location, Location, Location, a property show where the perfect home is sought for different buyers every week.

The inspiration for that satirical video is a recent interview with the Sunday Times, in which Allsopp said:

It's about where you can buy, not if you can buy. There is an issue around the desire to make those sacrifices.

What are these sacrifices that Allsopp speaks of?

When I bought my first property, going abroad, the EasyJet, coffee, gym, Netflix lifestyle didn't exist.

Allsopp, who bought her first home at the age of 21 with the support of her family, then illustrated her frugality:

I used to walk to work with a sandwich. And on payday I'd go for a pizza, and to a movie, and buy a lipstick.

As if there is one type of person who prefers “EasyJet, coffee, gym, Netflix” and another that likes walking, pizza, movie and lipstick.

Is Kirstie done? Sadly, no.

She goes on to suggest that young people can move in with their parents.

Is Kirstie Allsopp my Indian grandma in disguise? Nothing would please my grandma more than me moving back in with my parents and staying at home.

I’m already looking forward to Allsopp’s advice on dating: “stop swiping endlessly, let your parents pick a nice girl.”

Although she doesn’t realise it, Allsopp has provided a textbook example of a time-honoured tradition.

Almost every generation thinks successive generations are softer, lazier, and generally more disappointing, in comparison to their own.

Consider what Fortune magazine wrote in 1936, a mere three years before the start of WWII, the ultimate sacrifice event:

The present-day college generation is fatalistic. It will not stick its neck out. If we take the mean average to be the truth, it is a cautious, subdued, unadventurous generation.

A recurring feature of these intergenerational critiques is that they reference innovation and technology (i.e. the “Netflix” lifestyle) in a manner that confuses younger generations.

Why does this happen?

Morgan Housel, one of my favourite writers, convincingly argues that:

New technologies often spark cultural shifts towards ease and convenience, which for older generations are hard to distinguish from moral decline.

Or put another way, life is getting easier and older people are resentful. Resentful that young people don’t have to suffer in the same way that they did. Or worry about the same things they had to.

This narrative has unfolded in my own family. Like the children of many immigrants, my siblings and I have been raised on a rich oral history of our family’s struggles.

I’ve lost count of the number of stories where bricks are being thrown through the windows of their houses. School runs ending in being chased by National Front inspired gangs.

And if I had a pound for every time I heard one of these stories bookended with the phrase, “you don’t know the meaning of suffering,” I’d be able to afford a house for sure.

But as we condemn older generations and Kirstie Allsopp for their misguided and predictable criticisms of younger generations, it’s worth remembering that one day we will likely make the same errors as them.

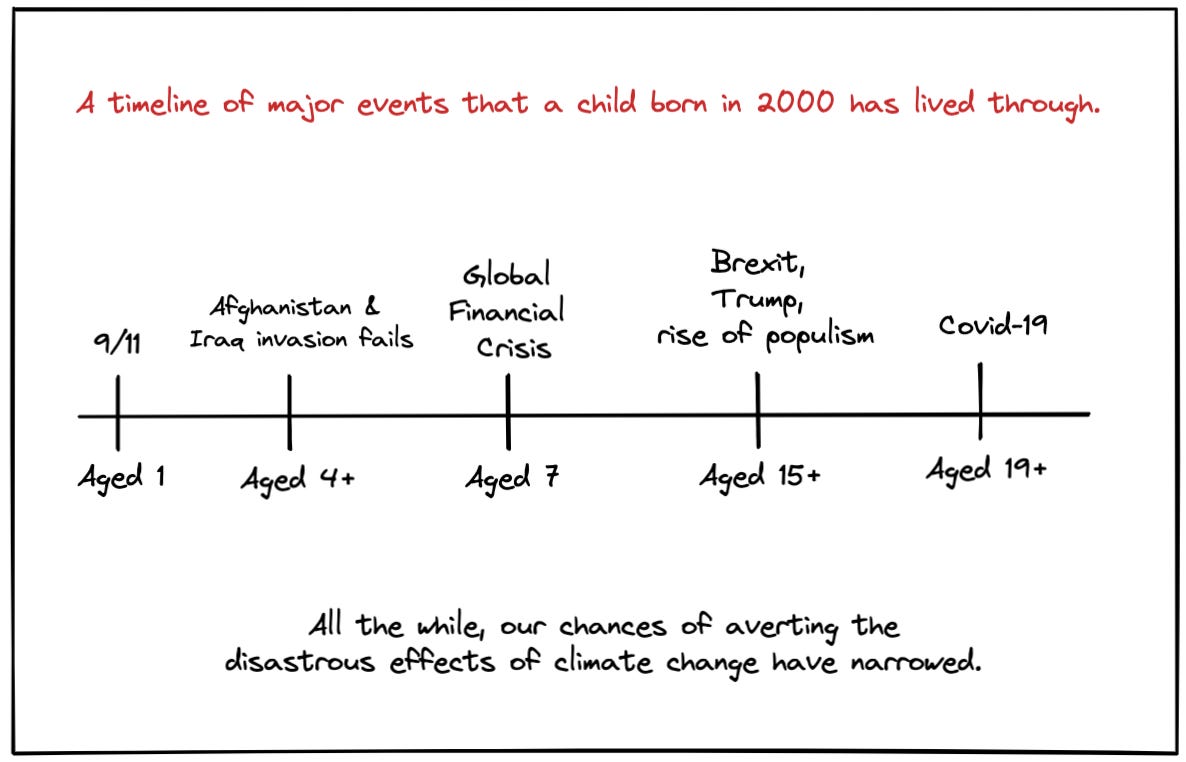

Consider the life of someone born in the year 2000.

Each generation knows its own suffering and uncertainty.

And every generation is destined to wave it in the face of those that follow.

So Kirstie, I forgive you for your tone-deaf remarks.