Politics With Skin In The Game

Hi friends 👋🏽 ,

Welcome back to Between Black and White, a monthly newsletter that challenges binary thinking by embracing complexity, with a focus on politics and society.

I've spent the month exploring futarchy, a type of governance which uses speculative markets to decide what policies to adopt.

While I'm not definitely not an advocate of futarchy, I was drawn to write about it because I'm interested in how new technologies can provide us with the means to reimagine our governance. Because as historian James Burke observed, “we live with institutions that were created in the past, using the technology of the past.”

You can read the essay below or click here to read it directly on my website.

Today, I’m also debuting my “Things I’m Thinking About” section. It’ll showcase some of the best thinking I’ve come across and provide some bitesize analysis to go along with it.

As ever, do get in touch if you have any thoughts. I love hearing from you.

Sunil

Things I’m Thinking About

Manufacturing Controversy

On March 25th, a cartoon of the Prophet Muhammad was shown in a class at Batley Grammar School. It sparked protests outside the school gates, while the teacher responsible was suspended. If you read the media coverage, you'd think that freedom of speech was under threat in the UK.

Except I don't think it was.

An excellent thread (link) by Jon Yates, author of forthcoming book, Fractured: Why our societies are coming apart and how to put them together again, highlights how the reaction was more about about signalling who we are (and aren't) and what we respect, rather than freedom of speech.

I don’t know what it was about March. Starting with Harry and Meghan's interview, we've been subject to events that we were told were highly significant. In reality, they were anything but. So much of the controversy in our politics seems to be needlessly manufactured at the moment. The recently released Sewell report on race relations in the UK is the latest example. As I wrote last year:

There is a childlike quality to our politics. We are shouting because they are shouting.

I have a theory that we secretly love moments where we can take on unnuanced viewpoints, egged on by media, in part because opportunities to do so are rare in our complicated world. We do so comfortably because we know deep down, that the stakes - at least for many of us - are in reality, low to non-existent. What do you think?

Future of Work = New Divides?

I'm thinking a lot about the future of work. Here's a recent thread of mine:

A History of Empire

I’ve been delving into Indian history this month sparked by Jason Hickel’s gripping book, Less Is More, in which he notes that between 1765 and 1938, over £32 trillion was siphoned out of India into British coffers. This is roughly an amount eleven times the current size of the UK’s economy. He observes:

Today, British politicians often seek to defend colonialism by claiming that Britain helped ‘develop’ India. But in fact exactly the opposite is true: India developed Britain.

I’m convinced that a more inclusive and thorough telling of Britain’s history in our schools would have a positive impact on our politics and public discourse. Fortunately, recent polling shows that 73% of White British and 75% of ethnic minority Britons agree that, “it is important that the history of race and Empire – including its controversies and complexity – are taught in British schools.” Over to you Boris.

Image of the Month

Politics With Skin In The Game

“The people of this country have had enough of experts,” proclaimed leading Brexiteer Michael Gove.

Like a vending machine offering only one flavour of cola, the experts, one after the other, had been warning UK citizens that voting to leave the European Union would lead to disaster.

Gove was right.

On June 23rd, 2016, 52% of UK voters looked past the warnings of the experts and signalled their desire to leave the EU.

Fast forward to today and after a torturous few years, we’ve ambled out of the EU.

If you’ve read the news recently, you’ll have seen that the scoreboard reads: “UK 1 - EU 0.”

We’ve put the vaccines in the back of the net.

But despite Boris Johnson’s promise of “the sunlit meadows beyond,” if you look at the fineprint, the score might be deceptive.

Buried by Covid-19, the UK’s departure has already reduced GDP by 0.5% in the first quarter of 2021, with exports hit by the disruption of supply chains. And while there is uncertainty, the Office for Budget Responsibility forecasts that in the longer-term GDP will be around 4% lower compared to a scenario where the UK stayed in the EU.

Whatever you think about Brexit, it illustrates the increasing disconnect between experts and voters.

Despite us knowing many of the policies that will lead to better outcomes in the longer-run, we don’t seem to vote for them.

Solving this conundrum is critical because we’re likely to again be faced with contentious issues in the future that our politicians may not be able - or may not want - to answer themselves.

Consider what Boris himself said on the morning of the Brexit vote: “there is no way of dealing with a decision on this scale except by putting it to the people.”

If Boris is right in suggesting that issues of this significance have to be decided by the people, perhaps it is time to reimagine how we use the wisdom of the crowd?

One such reimagination of how we might do this is futarchy, a form of governance first proposed in 2000 by Robin Hanson, an economist.

It uses the power of speculative markets to decide what policies to adopt.

Why isn’t our politics working?

Before explaining how futarchy works and the arguments for and against it, we need to understand the problems it’s trying to solve.

It’s answer to the following question:

Why don’t we adopt policies that we know will make our lives better?

Martin Gurri, a former CIA analyst, offers a compelling starting point in his 2014 book, The Revolt of The Public and the Crisis of Authority in the New Millennium. For Gurri, our politics has broken down because elites no longer control the flow of information.

Our institutions were designed at a time when information was scarce. Ordinary people were effectively told what the important issues were, as well as what to think about them.

But today, thanks to technology, we’re faced with a constant tsunami of information. Our elites no longer have the exclusive ability to tell us stories that explain the world.

Instead we’re all storytellers.

Truth and facts are contested like never before.

Everyone can claim to be an expert.

The result is that actual expertise is devalued and becomes harder to identify amidst the noise.

David Perell’s theory of the “paradox of abundance” captures how these dynamics play out:

The average quality of information is getting worse and worse. But the best stuff is getting better and better. Markets of abundance are simultaneously bad for the median consumer but good for conscious consumers.

But this takes us back to our starting point.

Why aren’t we being “conscious consumers” when it comes to politics? Especially when it has the power to shape our lives for better or worse.

Economist Robin Hanson, the inventor of futarchy, thinks the problem is our voting system.

Our vote rarely matters.

Because of this Hanson thinks we have weak incentives to search for information on the most effective policies, to listen to experts, and to demand that such policies are implemented.

Put simply, there is little pay-off for being a well-informed voter.

Hanson is right. In the UK, most of us have little influence when we vote.

First, with our first past the post electoral system, millions of voters are denied the representation they choose. In the UK’s 2019 General Election, the Green Party, Liberal Democrats and Brexit Party received 16% of votes, but only ended up with 2% of seats. First past the post effectively reduces our national politics into a two-party system.

Second, we can invert the question. How many votes do actually matter? If just 533 voters in marginal seats voted differently in the UK’s 2017 General Election, it would have changed the result.

Because of their limited influence, Hanson thinks voters are “rationally irrational,” adding that they are “not just ignorant, but overconfident in their political views and sources.”

In other words, they act against their own self-interests because their acts don’t really matter.

Henry Kissinger has a quote about university politics: “the reason that university politics is so vicious is because the stakes are so small.”

That perfectly summarises the core of Hanson’s argument:

In Hanson’s account, this leads to a situation where, “public policy seems closer to public opinion than to what relevant experts advise.”

If ill-informed voters are the malady, Hanson is offering what he thinks is the medicine: futarchy.

How does futarchy work?

Using speculative markets, citizens place bets on the likely effects of proposed policies. To paraphrase Hanson’s slogan, we vote on “values” (what to do), but bet on “beliefs” (how to do it).

Let’s see what this means in practice:

We vote, but not for our MPs. Instead we vote for a measure that we want to improve (what Hanson describes as the “value”). In this example, we voted to focus on GDP over unemployment.

Now comes the fun part.

Instead of kicking back on the couch and leaving our policymakers to it, we use speculative markets to decide which policies to adopt.

Policies that we think have the best chance of increasing our GDP (the “value” that we voted for). As we saw with Brexit, it may be that some people think leaving the EU will be just the tonic to increase our GDP.

And we’re off!

Over a period of time, any citizen can bet on how GDP will be affected as a result of this proposal (this is the part that Hanson calls “beliefs,” as we’re betting on how to increase GDP).

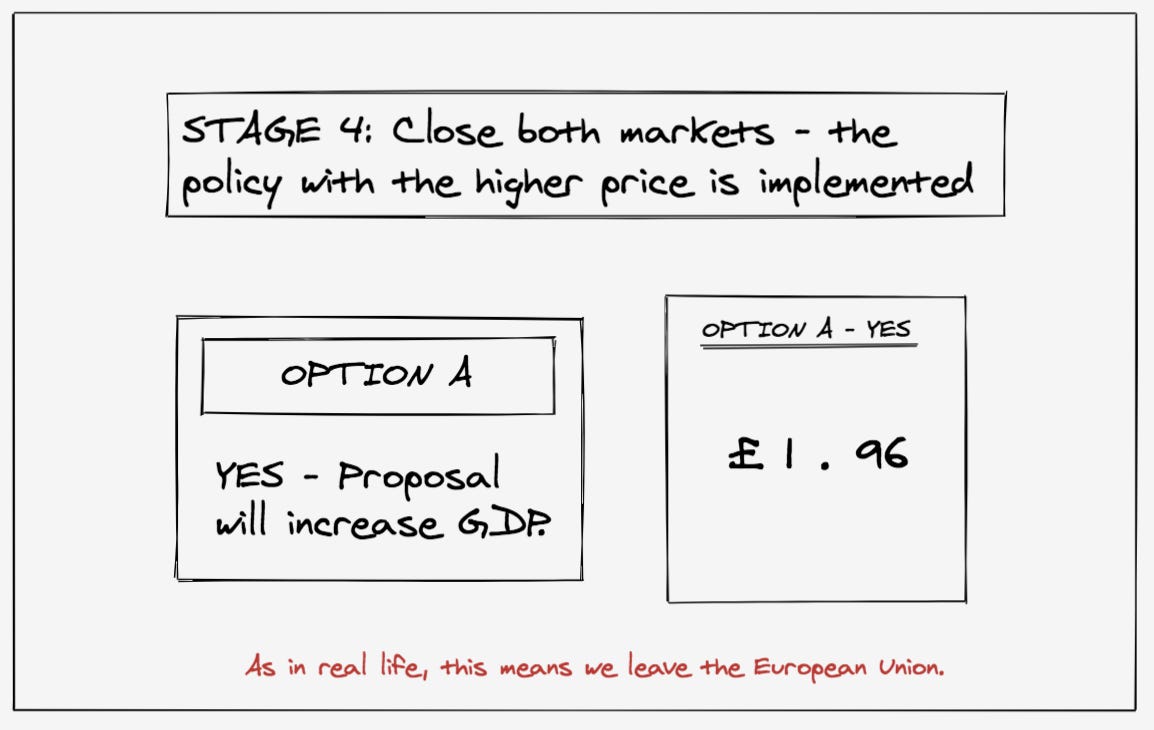

In this example, the higher price, £1.96, for Option A indicates that speculators think leaving the EU will lead to an increase in GDP.

This means the market thinks that the GDP after 15 years will be £1.96 trillion if we leave the EU. If we remain, GDP after 15 years is estimated to be £1.8 trillion (the price for “no”). This means the net present value of leaving the EU is estimated to be £160 billion - the difference between Options A and B.

The results are in! The higher price, £1.96, indicates that speculators think that leaving the EU will increase the UK’s GDP over the period. This policy is now implemented.

In this case, those who think that staying in the EU would have been better for GDP get their money back.

Now we wait…

This means the speculators were correct in their predictions.

Those who correctly forecast the change in GDP as a result of leaving the EU are rewarded.

Make Experts Great Again: The Argument For

Futarchy uses speculative markets to address the two problems we identified earlier:

How to create incentives for voters to be better-informed?

What information to value?

Let’s start with the incentives to being a better-informed citizen.

In a futarchy, there are strong financial incentives to be accurate. If you have information about a policy that others don’t have, perhaps because you’ve studied a policy in depth, you can profit from it. On the other hand, if you are wrong, you lose money.

It’s politics with skin in the game.

Because accuracy is valued and rewarded, this has a knock-on effect on what information is valued - and therefore consumed.

For starters, citizens may become less susceptible to the cognitive biases that plague our politics. Biases that can result in us giving too much weight to the wrong things, and backing ineffective policies.

For example, voters are often criticised for focusing on personalities at the expense of their policies. One example is the beer test, a recurring feature of US Elections, where people are asked which candidate they’d prefer to have a beer with. It first gained currency in 2004 when polling showed 57% of undecided voters would like to drink with Bush rather than Kerry.

A futarchy may lead to political activity being more focused on policies rather than personalities. Moving from a focus on spin - and our consumption of that spin - to activities like looking at models, statistical analyses and trading charts, because that’s where the informational edge exists.

And finally, in a futarchy, real expertise would likely be more valued than today. To repeat, people who are good at predicting outcomes are rewarded. The reverse is also true.

As Hanson says, “those who know they are not experts shut up, and those who do not know this lose money, and then shut up.”

There is perhaps some truth to this. Jean-Luc Bouchard, a writer, recently shared his experiences of using PredictIt, an online prediction market that offers exchanges on political and financial events. Bouchard observes:

“One of the things I soon learned was how easy it can be to mistake reading a lot about politics for having any honed ability to predict political outcomes ...

When your own money is on the line, you suddenly realize how often you’re wrong compared to how often you convince yourself that you were correct from the start. If I’d been forced to wager on every political event I confidently prognosticated over the past few years, I could easily imagine being deep, deep in the red.”

What’s particularly exciting in a futarchy is that anyone can become an expert, with actual results backing up their claims rather than today’s fuzzy status quo where it is impossible to validate many claims and counterfactuals.

We’ve already witnessed the emergence of a new generation of experts in other adjacent fields.

Consider the example of Brown Moses, a citizen journalist who founded bellingcat, whose investigations from Russia to Syria have generated more impact than many experts from traditional foreign policy backgrounds. Or Nathan Tankus, who hadn’t even finished his bachelor’s degree when he started writing about monetary policy. Today his newsletter is followed by some of the most influential financiers and economists in the world.

In a futarchy, it’s easy to imagine that a new crop of policy experts will emerge from unexpected places.

And over time, the quality of the prediction market in terms of picking winning policies may even improve as the experts who are rewarded the most become more influential.

So to recap, a futarchy creates financial incentives to be a better-informed citizen. This could transform our politics by:

Reducing our consumption of low-quality information and our susceptibility to cognitive biases - both of which distract us from what matters.

Making real expertise matter again - while democratising it.

Commodifying Politics: The Arguments Against

Having made the case for futarchy, I know what some of you are thinking: urgh!

If we are to reimagine our politics, surely we can do better than commodifying it? As the former Governor of the Bank of England, Mark Carney, writes:

“Commodification … can corrode the value of what is being priced… putting a price on every human activity erodes certain moral and civic goods.”

A market-based approach to politics like futarchy will likely erode the very principles that makes democracy powerful: equality and mass participation.

While I’ve illustrated that not everyone’s vote is equal in the UK, there is more equality in our one-person-one-vote electoral system than there would be in a futarchy.

We may all be able to vote for the value to focus on, but when it comes to betting on how we improve that value, there are grounds to suspect that the rich are more likely to participate than others. To begin with, they have more money and can capture more of the rewards within the market.

But they are also more likely to participate because they could buy policies that advantage them outside the realm of the speculative market. They can do this by purchasing yes options en masse and shorting selling no options. In doing so, they would increase the price of “yes,” while driving down the price of “no.” Even if they aren’t bad rich actors, this is a problem.

There are other reasons to be sceptical of futarchy:

Will the Market Actually Work? Given the long time horizons (fifteen years in our example), there are doubts whether it's possible to accurately forecast the impact of a policy. This is especially because some students of prediction markets have asserted that they only actually become accurate as they near settlement. If this is true, the core assumption in a futarchy - that a speculative market can forecast the impact of a policy well in advance of an outcome - falls apart.

Even if this criticism does not hold, how does a futarchy account for the impact of unpredictable events on the value like a pandemic?

And if multiple policies are implemented, how do you assess the causal relationship between a specific policy and the value? In a futarchy, you may be focused on the impact on GDP, but you still want to know what policies are working (or not). This inability to establish a causal relationship means that scenarios could arise where speculators are rewarded despite backing politics that decreased the value.

The Problems With One Value To Rule Them All. Can we agree on one value to work towards? Is that even desirable? After all, we have a poor track record on picking values. For example, we tend to measure our societies success with GDP, something that even the creator of GDP, Simon Kuznets, warned against doing!

The campaign to vote for a value might also be swayed by the very same problems futarchy is trying to address: ill-informed citizens voting on basis of flawed information and biases. It also presents an opportunity for bad actors to influence the choice of value. If the wrong value is selected, there will be a problem at the root of the futarchic system.

We’re Not Rational. Futarchy is rooted in rational choice theory. Rational choice theorists argue that much of politics can be explained in terms of voter self-interest, rather than factors like history and culture. When it comes to voting this theory assumes that voters pursue their interests rationally. But we don’t behave like that in reality.

In the days after Brexit, for example, many Remainers mocked the perceived stupidity of Brexit voters, for harming the very economy they depended on. This was especially the case when it came to the voters of Sunderland, who voted to leave despite one of Sunderland’s major employers, Nissan, warning that exiting the EU would put 6,700 jobs in the city at risk along with their factory worth almost £4bn.

It’s an example of the problem futarchy aims to solve. We, the voter, voting for something that makes us feel good that might not create an overall long-term positive outcome.

But it’s also an example of what futarchy misses. For many, the vote to leave the European Union was about much more than the economy. With its focus on one value, futarchy could advance a reductive model of human behaviour (“homo economicus”) that has already been challenged as outdated.

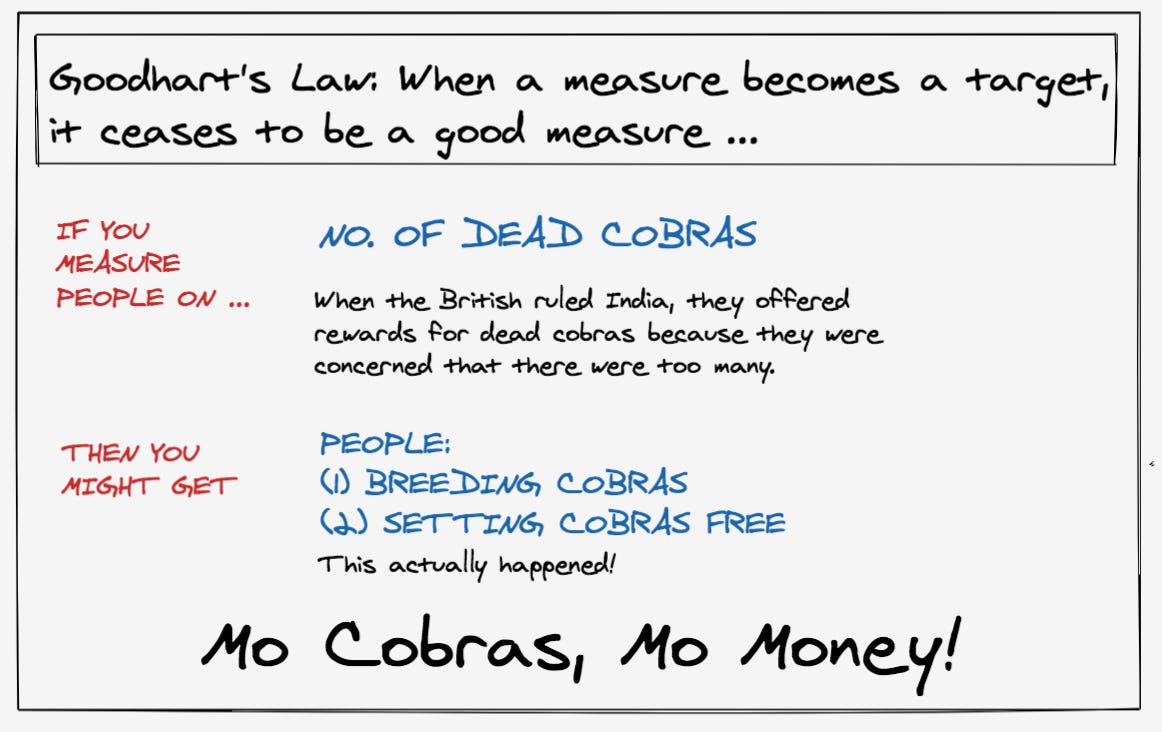

Unintended Consequences. Goodhart’s Law states that when a feature of the economy is picked as an indicator of the economy, it ceases to function as an effective indicator because people start to game it.

A futarchy would embed Goodhart’s Law into the core of our governance system, with people optimising for that value regardless of the consequences - likely resulting in other policy failures we don’t even anticipate.

Entrenching A Technocratic Top-Down Model of Policymaking. In 2019, Dominic Cummings wrote a blog about high-performance government that explored the idea of “seeing rooms.” These are Nasa-like control centres designed to support policymakers to make decisions in complex environments.

Futarchy seems to fit into the world of “seeing rooms.” Turn a few nobs here and there. And hey presto, we’ve got better outcomes!

But our policymaking may be failing precisely because of such simplistic thinking. Here’s Polly Mackenzie, CEO of think tank Demos, to explain why:

[There is] an affliction that runs right through the heart of policymaking. We build models and spreadsheets to establish what the impact of a policy might be. To fit into those spreadsheets, the people have to be grouped into categories of similar people, and then all the inconvenient and incompatible details of their lives have to be stripped away. And that’s when we’re doing things properly. Half the time, we simply make an assumption that everyone in the population is very much like us.

Put simply, futarchy may embed a top-down approach to policymaking that many argue is ill-equipped to navigate the complexity of the real world and one that is already responsible for policy failures.

So despite the purported benefits offered by a futarchy, such a system poses several problems including:

The risk of bad actors manipulating the market and the threat to mass participation;

Doubts whether the market would actually function as theorised;

The fact that futarchy is rooted in a model of human behaviour that doesn’t align with how we behave in reality, especially when it comes to politics;

The likelihood that the selection of a value to optimise will lead to unintended consequences; and

The continuation of an approach to policymaking that won’t work.

This is not an exhaustive exploration of the pitfalls of futarchy. If you want to read more, check out this post by Paul Hewitt.

The Future is Already Here. But Which Future?

Our institutions need to evolve.

As historian James Burke has observed, “we live with institutions that were created in the past, using the technology of the past.”

But as we’ve seen, futarchy isn’t the answer to our democratic woes.

In an essay arguing that Big Tech is more competent than the US government, Byrne Hobart writes:

Idealists believe that every institution exists to build a better future for its participants. Cynics think every institution exists to perpetuate its own existence for the current benefit of whoever is in charge. The realist approach is to accept the cynical view as the ultimate asymptote to which all institutions trend, and to create incentives that align cynical self-preservation with prosocial behavior.

With its attempts to align the selection of better policy outcomes to financial rewards, it’s clear that futarchy’s intellectual roots lie in a realist approach to the world. But if we are to reform our institutions, we must offer up a more hopeful vision for cooperation that drives collective action.

Perhaps most problematic of all is that futarchy is emblematic of an approach to improving our politics that sees markets as a panacea to our problems, when in fact, its workings may be the cause of many of our problems.

Despite focusing on how a better use of information can lead to improved decision making, Hanson misses an obvious information problem. That is, the long-standing failure of our markets to reflect the externalities of economic activity in their pricing. From slavery right through to the present-day extraction of natural resources, the costs of our economic activity have rarely included all the costs.

This missing information has profoundly shaped capitalism. As Daniel Gross, founder of Pioneer, has said, “capitalism maximises for what’s great today, not for what’s good for ten years from now."

Proper accounting of externalities would likely have a greater net positive impact on our policymaking than the implementation of a futarchy.

Despite being skeptical of futarchy, we’re at a moment where innovation in our governance system is within reach. In fact, some of the most interesting experiments are taking place in the world of cryptocurrencies, where decentralisation and new technologies are colliding to generate new possibilities. To paraphrase William Gibson, I’m convinced the future is already here, we just have to keep searching for it.